Optimising a Molecular Dynamics Application

The full source code is available on GitHub.

Problem Statement

The second part of the Performance Programming module (EPCC11009), was to manually optimise a C-based molecular dynamics simulation code. The project required the transformation of a suboptimal legacy codebase into a high-performance solution, prioritising runtime reduction without compromising the integrity of the simulation results. A key restriction imposed by the project was that all optimisations must be done using a single thread i.e no multi-threading.

Hardware and Tools

The project was conducted on the Cirrus UK Tier-2 HPC service, utilizing a single standard compute node. The node is powered by dual 18-core Intel Xeon E5-2695 v4 (Broadwell) processors running at 2.1GHz, providing a total of 36 physical cores and 72 hardware threads backed by 256GB of shared memory.

To contextualize the optimization strategy, it is important to note the cache topology: each core possesses a private 64KiB L1 cache (split evenly between instructions and data) and a 256KiB L2 cache, while the sockets feature a substantial 45MiB shared L3 cache.

Compilation

The Intel oneAPI compiler (version 2024.0.2) was used (provided by oneapi

and compiler/2024.0.2 Lmod modules on Cirrus), as it delivered the best

performance in a previous investigation using the compiler flags shown below.

These flags are, therefore, used for compiling the code using -std=c11,

targeting the Intel Broadwell architecture with the optimisation level

-O3. Additionally, the program is configured to run solely on a single

thread as the code modifications focused on improving the serial performance.

icx -Wall -axBROADWELL -march=broadwell -mtune=broadwell -O3 -ipo -qoverride -limits

Correctness Testing

The application was executed on Cirrus using the Slurm workload manager

(v22.05.11). Performance analysis was conducted with Intel VTune 2024.0.0

(vtune/2024.0) and gprof v2.30-93.el8, while memory analysis was performed using

Valgrind v3.22.0. Each test was conducted three times, with the average and

standard deviations recorded to ensure consistency and accuracy in the results.

Additionally, correctness was verified using the diff-output tool

provided as part of the code to ensure the generated output.dat files

contained values below the 0.001 threshold. The program was further extended to

detect NaN values using the isnan function from the C standard

library.

Preliminary Performance Analysis

Previous optimisation work established a baseline runtime of 64.493 seconds using the unmodified source code and specific compiler flags. However, initial replication attempts yielded an unexpected regression to 74.342 seconds (a ~10s increase). This discrepancy was traced to a system update on Cirrus, where the default Intel compiler had shifted from ICX 2024.0.2 to 2025.0.4. The newer version proved less efficient with the established flag configuration. To ensure a consistent baseline, the environment was explicitly pinned to the compiler/2024.0.2 module, which restored the expected runtime.

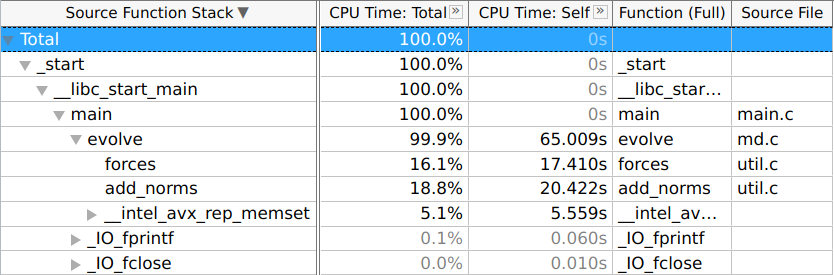

Prior to manual optimisation, the application was profiled using a 4096-particle

simulation. The -fno-inline flag was applied alongside -O3 to

preserve the call graph structure during analysis. VTune Hotspot analysis

identified the evolve function as the primary bottleneck, consuming 99.9%

of total execution time. Within evolve, the functions forces,

add_norms, and __intel_avx_rep_memset accounted for 43.391s.

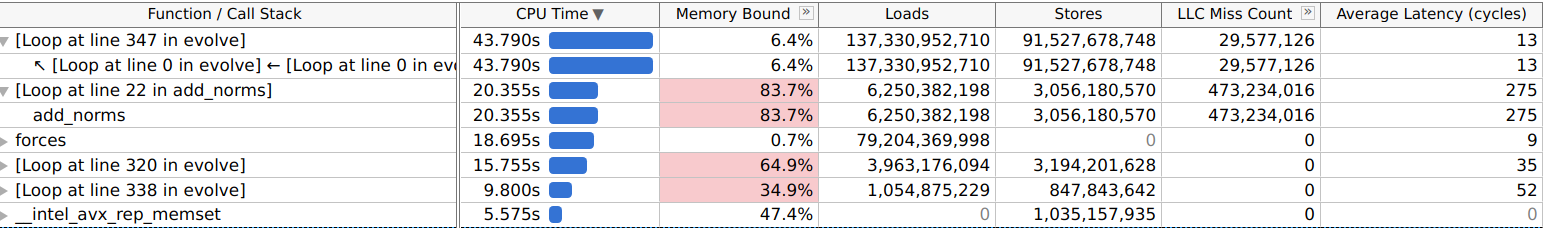

Memory usage and access patterns were also analysed

(-collect-memory-access). The results obtained, as shown below, indicate

the primary performance bottleneck can be attributed to memory-bound operations.

Specifically, the add_norms function reported being 83.7% memory-bound,

with a last-level cache miss rate of 94.1% (473,234,016 misses) and an average

access latency of 275 cycles, resulting in 20.355 seconds spent within that

function. Additionally, the code that calculates pairwise forces accounts for

43.790 seconds of the total runtime. Although the profiler did not explicitly

identify this section as memory-bound, the likely causes may still be

inefficiencies related to memory access patterns and the pow function,

which can be computationally expensive if the compiler cannot optimise it

effectively.

Valgrind was also used to identify issues related to memory allocation. Running

the program with the -ggdb3 flag, revealed that a total of 608MB

(637,960,192 bytes) were allocated across 9 blocks. The output indicated that

none of these blocks, allocated through calloc, were freed before the program

terminated, resulting in memory leaks.

valgrind --leak -check=full --show -leak -kinds=all --track -origins=yes

--verbose ./ build/md

Code Optimisations

Based on the performance results obtained through profiling, this section

presents several recommendations for code modifications to enhance the program’s

performance. The optimisations focus on the evolve function, aiming to

minimise unnecessary loop iterations, improve memory access efficiency, simplify

calculations, and reduce the overall memory footprint.

Loop Fusion

Loop fusion involves merging independent loops to reduce the total number of

iterations. The evolve function contains 20 for-loops, many of which can

be fused. This optimisation not only decreases the number of executed iterations

but also enhances compiler optimisation opportunities, improving overall

performance. The first recommendation is for the viscosity and wind terms, as

well as the central mass distance to be combined. This is possible as each

function iterates over Ndim times with this initial fusing of loops shown

below. Furthermore, instead of setting each value to zero for the r array, this

can be replaced with a call to memset before the first loop.

memset(r, 0, sizeof(double) * Nbody);

for (int i = 0; i < Ndim; ++i) {

vis_forces(Nbody , f[i], vis , velo[i]);

wind_forces(Nbody , f[i], vis , wind[i]);

add_norms(Nbody , r, pos[i]);

}

Each function separately loops over the Nbody array, which can be avoided

by extracting the code of each function out directly into the evolve

function, reducing the Nbody iteration count by a third.

memset(r, 0, sizeof(double) * Nbody);

for (int i = 0; i < Ndim; ++i) {

for (int j = 0; j < Nbody; ++j) {

f[i][j] = -vis[j] * velo[i][j]; // vis_forces()

f[i][j] = f[i][j] - vis[j] * wind[i]; // wind_forces()

r[j] += (pos[i][j] * pos[i][j]); // add_norms()

}

}

At this stage, it was observed that looping over each dimension individually

made it challenging to fuse loops due to dependencies such as the use of

sqrt and the addition of pairwise forces. To address this, rather than

iterating over each particle dimension separately, the loops were restructured

to process entire particles i.e x, y, z in one go. The result of this

transformation, eliminates the need for memset and allows the central force

calculation to be combined into the force calculation loop.

Whilst this is initially inefficient, we later change the memory layout of particles to better align with our accesses.

for (int i = 0; i < Nbody; ++i) {

f[0][i] = -vis[i] * velo [0][i]; // viscosity

f[0][i] = f[0][i] - vis[i] * wind [0]; // wind

// X and Y here ...

r[i] = 0.0;

r[i] += (pos [0][i] * pos [0][i]);

r[i] += (pos [1][i] * pos [1][i]);

r[i] += (pos [2][i] * pos [2][i]);

r[i] = sqrt(r[i]);

f[0][i] -= forces(G * mass[i] * M_central , pos [0][i], r[i]);

f[1][i] -= forces(G * mass[i] * M_central , pos [1][i], r[i]);

f[2][i] -= forces(G * mass[i] * M_central , pos [2][i], r[i]);

}

With this change in place, further analysis revealed that calculating the

pairwise and normalised separation vector can be fused into the pairwise

addition directly. This is due to Npair loop that iterates over particle

pairs being identical to that of the inner for-loop of the adding of pairwise

forces int j = i + 1; j < Nbody; ++j. Therefore, the Npair loop can

be removed and placed in the innermost loop, resulting in fewer additional

iterations needed.

int k = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < Nbody; ++i) {

for (int j = i + 1; j < Nbody; ++j) {

// For separation for each dimension

delta_pos [0][k] = pos [0][i] - pos [0][j];

delta_pos [1][k] = pos [1][i] - pos [1][j];

delta_pos [2][k] = pos [2][i] - pos [2][j];

// Squared norm calculation

delta_r[k] = 0.0;

delta_r[k] += (delta_pos [0][k] * delta_pos [0][k]);

delta_r[k] += (delta_pos [1][k] * delta_pos [1][k]);

delta_r[k] += (delta_pos [2][k] * delta_pos [2][k]);

delta_r[k] = sqrt(delta_r[k]);

// Flip forces ...

if (delta_r[k] >= size) {

...

The last loop fusion that can be applied is at the end of the evolve function, where the position and velocity can also be combined.

for (int i = 0; i < Nbody; ++i) {

for (int j = 0; j < Ndim; ++j) {

pos[j][i] += dt * velo[j][i];

velo[j][i] += dt * (f[j][i] / mass[i]);

}

}

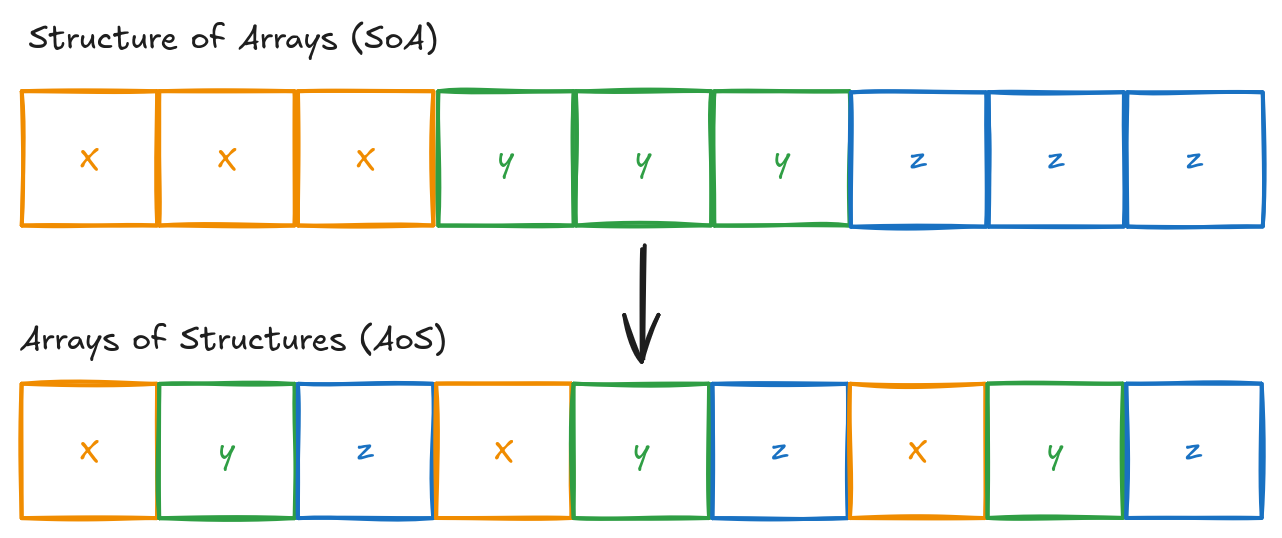

Loop Interchange

Loop interchange refers to reordering nested loops to enhance cache locality. During initialisation, arrays are allocated as a contiguous one dimensional block of memory, with the particle layout illustrated below. This arrangement follows the Structure of Arrays (SOA) approach, storing each component continuously within a single buffer. Several loops in the original evolve function iterate over loops in column-major order, which results in poor cache usage. These are swapped so that memory accesses are instead in row-major order. It is important to note, however, that this is an intermediate step as the memory layout is later changed to an Array of Structures (AOS).

The loops that calculates the central force, can be swapped so that accesses

into the f and pos arrays are continuous in memory.

for (int i = 0; i < Ndim; ++i) {

for (int j = 0; j < Nbody; ++j) {

f[i][j] -= forces(G * mass[j] * M_central , pos[i][j], r[j]);

}

}

This can also be applied to the updating of positions and velocities:

for (int i = 0; i < Ndim; ++i) {

for (int j = 0; j < Nbody; ++j) {

pos[i][j] += dt * velo[i][j];

velo[i][j] += dt * (f[i][j] / mass[j]);

}

}

Algebraic Simplification

The code’s performance and readability can be substantially improved by performing algebraic simplification. Firstly, the code shown previously:

f[i][j] = -vis[j] * velo[i][j]; // vis_forces()

f[i][j] = f[i][j] - vis[j] * wind[i]; // wind_forces()

r[j] += (pos[i][j] * pos[i][j]); // add_norms()

can be simplified by combining the viscosity and wind terms into a single equation by applying the distributive property of multiplication: $ a ⋅ b + a ⋅ c = a ⋅ (b+c) $.

$ \vec{F} = -u ⋅ \vec{V} = -u ⋅ (\vec{v} + \vec{w}) $

where $ u $ is the viscosity and $ V $ is the effective velocity vector, the combination of velocity $ v $ and wind vector $ w $. Additionally, this simplification more directly maps to a Fused Multiply-Add (FMA) instruction, enabling supported hardware to compute each component force in a single instruction.

f[i][j] = -vis[j] * (velo[i][j] + wind[i]);

Next, as the central mass distance calculation is fully fused, the r array is now redundant as this is the only location where this is calculated. Therefore, this can be changed to be entirely on the stack using a single double-precision variable:

double r = sqrt(pos_x*pos_x+pos_y*pos_y+pos_z*pos_z);

As identified during profiling, the pow function caused significant

bottlenecks, resulting in runtimes of over 20 minutes, likely due to needing to

handle raising to any power. Since the code hardcodes raising to the third

power, the forces function for the central force calculation is extracted

and the call to the pow function is replaced by three multiplications.

Additionally, the Wv and r_pow_3 are cached as the values do not

change between the components.

// calculate central force

double Wv = G * mass[i] * M_central;

double r_pow_3 = r*r*r;

f[0][i] -= Wv * pos [0][i] / r_pow_3;

f[1][i] -= Wv * pos [1][i] / r_pow_3;

f[2][i] -= Wv * pos [2][i] / r_pow_3;

Next, after fusing the pairwise separation and norm calculations into the

addition of pairwise forces, it was initially observed that the runtime

increased from 13 to 21.9 seconds per 100 iterations, likely due to the compiler

being unable to optimise effectively. However, these modifications highlighted

that the delta_pos and delta_r arrays were redundant and could be

replaced with stack-allocated five variables. By applying algebraic

simplification and eliminating unnecessary array loads and stores, the runtime

of the program was significantly reduced. Additionally, instead of diving three

times, which is substantially slower than multiplication, we can compute the

inverse once and use this precomputed value for all dimensions. Introducing the

sign variable simplifies the code substantially as the forces do not need to be

duplicated for the positive and negative forces. The updated pairwise particle

calculation reduced runtime per 100 iterations to approximately 6.4 seconds on

average.

double dx = pxi - pxj, dy = pyi - pyj, dz = pzi - pzj;

double delta_r = sqrt(dx * dx + dy * dy + dz * dz);

double size = radius[i] + radius[j];

double Wv = G * mass[i] * mass[j];

double inv_r3 = 1.0 / (delta_r * delta_r * delta_r);

double F = Wv * inv_r3;

double fx = F * dx, fy = F * dy, fz = F * dz;

double sign = (delta_r >= size) ? -1.0 : 1.0;

f[0][i] += sign * fx; f[0][j] -= sign * fx;

f[1][i] += sign * fy; f[1][j] -= sign * fy;

f[2][i] += sign * fz; f[2][j] -= sign * fz;

if (sign > 0)

++collisions;

Additionally, the k increment variable can be removed since Ndim

is no longer used. Likewise, the hascollided variable is unnecessary, as

collisions can be incremented directly.

Redundant Memory Allocations

Now that the heap-allocated r, delta_r and delta_pos arrays

are no longer used, they can be removed, saving 512MB of memory when simulating

4096 particles. This shows that recalculating values on the stack can not only

significantly improve performance but also eliminate the need for redundancy

arrays and therefore, reduce memory usage. The f, pos, and

velo arrays were two-dimensional, where the first index represented the

spatial dimension and the second indexed individual particles. This was

restructured into a one-dimensional allocation to eliminate an extra pointer

dereference for each load and store operation. Additionally, the memory layout

was transformed into an Array of Structures (AoS) format, interleaving particle

positions as (x1, y1, z1), (x2, y2, z2). This new structure aligns better with

the applied code optimisations, leading to a measurable performance improvement:

the average runtime for 500 iterations was reduced from 6.49 to 5.95 seconds,

equating to an improvement of approximately 0.548 seconds per 100 iterations.

The new formula for indexing can now be expressed as $ 3i + d $ where $ i $ is

the particle index ($ 0 ≤ i < N $ body) and $ d $ is the dimension (1, 2, 3).

Furthermore, Valgrind’s analysis conducted as part of the preliminary analysis

revealed memory leaks, prompting the addition calls to free to ensure

that all memory allocated via calloc is properly freed at the end of the

program.

free(mass);

free(vis);

free(radius);

free(f);

free(pos);

free(velo);

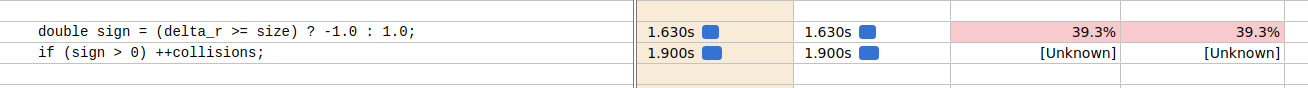

Branchless Sign

Intel VTune revealed a significant portion of execution time was spent on the two if-statements within the pairwise addition suggesting slowdowns likely as a result of branch misprediction.

A branchless version of this can be implemented using the copysign

function, reducing the runtime per 100 iterations from 5.94 seconds to 4.85

seconds, resulting in a total execution time of 24.34 seconds.

double sign = copysign(1.0, size - delta_r);

collisions += (sign > 0);

Results

After implementing numerous optimisations, the performance between the original unoptimised and newly optimsied code is compared with particle counts ranging from 128 to 16,384 (doubling at each step). As shown in the table below, the runtime exhibited a superlinear increase, primarily due to growing array sizes exceeding lower cache levels, leading to higher memory access latency. The optimised scaling results, demonstrate significant improvements across all particle counts. Notably, the application can now simulate four times as many particles within roughly the same duration.

| Particle Count | Unoptimised Time (s) | Optimised Time (s) |

|---|---|---|

| 128 | 0.1068 | 0.00512 |

| 256 | 0.3238 | 0.01973 |

| 512 | 1.1180 | 0.07823 |

| 1024 | 4.2282 | 0.27985 |

| 2048 | 19.2267 | 1.09915 |

| 4096 | 77.5005 | 4.38526 |

| 8192 | 322.3570 | 16.06 |

| 16384 | 1077.3330 | 64.00 |

| Metric | Unoptimised | Optimised | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elapsed Time (s) | 67.553 | 25.618 | +2.64x |

| CPU Time (s) | 64.493 | 24.205 | +2.66x |

| Memory Bound (%) | 34.9 | 13.2 | +2.64x |

| L1 | 6.8 | 18.2 | +2.68x |

| L2 | 2.5 | 2.3 | +1.09x |

| L3 | 1.6 | 0.0 | - |

| DRAM Bound (%) | 13.7 | 0.0 | - |

| Store Bound (%) | 17.1 | 0.0 | - |

| Loads | 228,405,133,696 | 21,991,521, 297 | +10.39x |

| Stores | 100,015,973,815 | 3,206, 480,225 | +31.19x |

| LLC Misses | 502,811,142 | 0 | - |

| Avg. Latency (cycles) | 20 | 9 | +2.22x |

The final evolve function is shown below:

int hit_count = 0;

for (int step = 1; step <= count; ++step) {

printf("timestep %d\n", step);

printf("collisions %d\n", hit_count);

// set the viscosity term in the force calculation

// add the wind term in the force calculation

for (int i = 0; i < nbody; ++i) {

double px = pos[i].x, py = pos[i].y, pz = pos[i].z;

double vx = velo[i].x, vy = velo[i].y, vz = velo[i].z;

double Wv = gravity * mass[i] * central_mass;

double r = sqrt(px*px + py*py + pz*pz);

double r_pow_3 = r * r * r;

double fx = -vis[i] * (vx + wind.x);

double fy = -vis[i] * (vy + wind.y);

double fz = -vis[i] * (vz + wind.z);

f[i].x = fx - (Wv * px / r_pow_3);

f[i].y = fy - (Wv * py / r_pow_3);

f[i].z = fz - (Wv * pz / r_pow_3);

}

// Add pairwise forces

for (int i = 0; i < nbody; ++i) {

for (int j = i + 1; j < nbody; ++j) {

double dx = pos[i].x - pos[j].x;

double dy = pos[i].y - pos[j].y;

double dz = pos[i].z - pos[j].z;

double delta_r = sqrt(dx * dx + dy * dy + dz * dz);

double size = radius[i] + radius[j];

double Wv = gravity * mass[i] * mass[j];

double inv_r3 = 1.0 / (delta_r * delta_r * delta_r);

double F = Wv * inv_r3;

double fx = F * dx , fy = F * dy , fz = F * dz;

double sign = copysign (1.0, size - delta_r);

hit_count += (sign > 0);

f[i].x += sign * fx;

f[i].y += sign * fy;

f[i].z += sign * fz;

f[j].x -= sign * fx;

f[j].y -= sign * fy;

f[j].z -= sign * fz;

}

}

// update positions and velocities

for (int i = 0; i < nbody; ++i) {

pos[i].x += dt * velo[i].x;

pos[i].y += dt * velo[i].y;

pos[i].z += dt * velo[i].z;

velo[i].x += dt * (f[i].x / mass[i]);

velo[i].y += dt * (f[i].y / mass[i]);

velo[i].z += dt * (f[i].z / mass[i]);

}

}

*collisions = hit_count;

Additional optimisations could be implemented in the future to further reduce the runtime including manual SIMD vectorisation as well as multi-threading with OpenMP.

Full source code including the unoptimised and newly optimised version is available on GitHub.